Survey and Excavations at Chiddingfold Villa 2002-2008

For some years now David and Audrey Graham have been undertaking fieldwork on the site of the building complex at Whitebeech, Chiddingfold in order to gain a better understanding of this enigmatic site. What follows is the text of a recent report to English Heritage dealing with the outcome of a geophysical survey. The report contains a useful summary of what has been achieved to date.

Summary

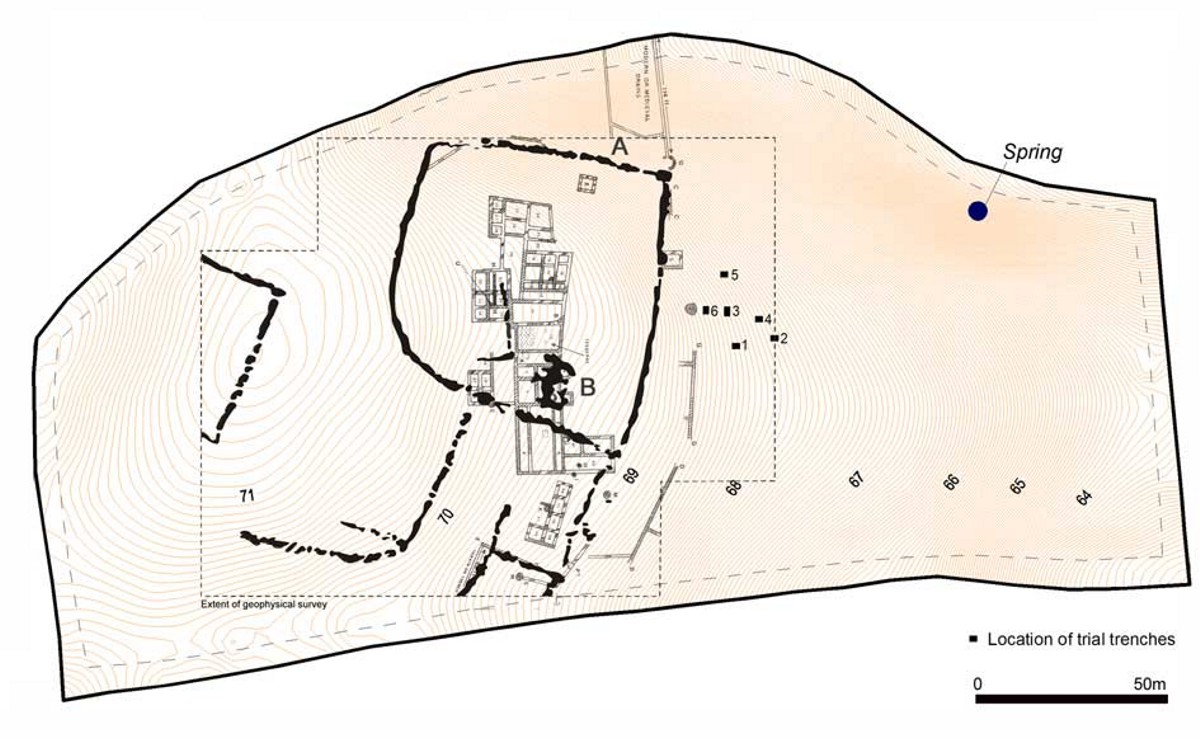

A geophysical survey using a magnetometer was carried out on the site of the Roman buildings at Whitebeech, Chiddingfold, that were discovered in the 19th century. The survey was intended to establish the exact location of the buildings within the field. The results, when compared with the 19th century excavation plan and correlated with the results of an earlier fieldwalking programme, provide a fair degree of confidence as to the location of the buildings. Evidence was also found for an underlying, presumably pre-Roman, D-shaped enclosure with subsidiary rectangular enclosures adjoining an apparent entrance trackway.

Introduction

The Roman buildings at Whitebeech, Chiddingfold; Scheduled Monument no SU 135) are sited on a slight east-facing artificial terrace just below the top of a prominent hill and within a field known as The Riddings. The countryside surrounding the hill is Weald Clay but the hill itself is capped by loam. The site was discovered in 1883 during agricultural works and was subsequently excavated, but the results were not finally published until 1984 (Cooper et al 1984). The report, including a plan of the buildings, while of a good standard for the period, fails to note phasing, stratigraphy or even to give the exact location of the buildings within the field.

In 2002 Surrey Archaeological Society, with Scheduled Monument Consent, carried out a gridded survey of the field recording all surface material within each 10m square – the material being returned to the square of origin after on-site recording. This exercise clearly showed the likely position of the Roman buildings and allowed a ‘best fit’ to be made relating the 19th century plan to the distribution of finds noted during the fieldwalking (Howe et al 2002).

In 2005 a team from Surrey Archaeological Society excavated six small trenches over an isolated scatter of tesserae in the plough-soil about 30m east of the presumed site of the main range of Roman buildings (see location plan). Further tesserae were recovered from the plough-soil level in all the trenches, but only two produced definite evidence for underlying archaeology. One trench (3) contained a stone-packed post pit c 0.8m in diameter and partially backfilled with tesserae, while a second (6) – that closest to the previously excavated Roman buildings – exposed a layer of building rubble.

In 2008 the authors, again with consent from English Heritage, carried out a magnetometer survey on the presumed site of the Roman buildings, in an attempt to confirm their exact location. The survey, when taken with the results of the gridded fieldwalking, now allows a fair degree of certainty as to the location of the buildings. Clear evidence was also found for a, presumably earlier, D-shaped enclosure, together with subsidiary rectangular enclosures and an apparent entrance trackway.

Method

In 2002 a grid, linked to the Ordnance Survey grid was laid out across the field using a Topcon 211 total station. All subsequent work including the geophysical survey has been linked to this grid, making the results spatially comparable.

For the purposes of the geophysical survey, a grid of 30m squares was laid out and surveyed using a Geoscan FM256 fluxgate gradiometer at 1m traverse intervals with a 0.25m sampling interval and zig-zag traverses. The survey data were processed using Geoplot 3.0 software. The area was generally magnetically quiet, however the exposed nature of the site and the strong gusting winds and rain during the survey affected the quality of the results. This meant that the data had to be rectified using zero mean traverse and a low pass filter and the results were then interpolated to 0.25m resolution across the traverses and printed as a compressed shade plot.

Results

The site is unusual in that, in this case, excavation (in the 19th century) preceded the geophysical survey rather than the usual order of events. This has allowed elements of the survey to be interpreted in the light of the excavation plan and report.

The results of the survey are shown on the accompanying interpretation/ location plan has been overlaid with the ‘best fit’ for the Roman buildings (the 19th century excavation plan).

As can be seen, the main feature revealed by the survey is the c 70 x 70m D-shaped enclosure, which partially surrounds and underlies the Roman buildings. The latter assumption is because the Rev Cooper, the original excavator, makes no mention of a destruction line through the buildings and it therefore seems probable that the buildings post-date and overlie the enclosure.

Curving south-west from the D-shaped enclosure and turning west is a second linear feature, which appears to be paralleled to the south-east for part of its length by a second linear. Though rather wide, this may be a trackway leading to the enclosure with at least two rectangular enclosures lying immediately to the south-east.

Within the D-shaped enclosure are two straight linear features forming a right angle, the longer side more or less lining up with the long axis of the main Roman building. It is uncertain whether this relates to the building or to some other feature. On the computer screen, it is possible to discern a number of other potential lines in this general area but none is clear enough for there to be any certainty as to their meaning or even their true existence.

A stretch of ditch marked A (see location plan) shows a high response indicative of heating and it is interesting that this appears to lie close to ‘circular structure Q’ (Cooper et al 1984, 71) a feature found in the 19th century excavations and which the excavator thought to ‘have been a furnace’. He goes on to say ‘The earth here was very black, and for a distance of upwards of 12 feet on the west side’. Equally, the area of high magnetic response marked B on the location plan lies close to an area of the buildings identified as having a furnace and hypocaust. The shape of the response, having a central ‘spine’ with four cross ‘bars’, may possibly be the result of the physical layout of such a heating system, although it would seem rather large. The highest magnetic responses came from either end of the northernmost cross ‘bar’ and may possibly represent the original fireboxes. Only excavation will resolve this question.

The separate and differently aligned suite of rooms to the south of the main Roman building, labelled 44 – 48 on Cooper’s plan, appears to lie neatly within one of the rectangular enclosures and it may be that rather than being a coincidence it is the earliest Roman building on the site and utilises a pre-existing enclosure.

To the west of the main features the survey recorded three sides of a straight-sided feature, the longest recorded side of which was c 40m in length. As it was not possible to continue the survey to the west in the time available the nature and extent of this feature remains unknown.

A public footpath runs along the southern edge of the field and has cut a deep groove into this section of the slope of the hill. It has often been claimed that this path is of great antiquity, and it may be worth noting that since it appears to cut through the southernmost rectangular enclosure, it would seem likely to post-date that enclosure – giving some idea of an earliest possible date for the path.

Conclusions

While the survey failed conclusively to show the walls of the Roman buildings, it nevertheless confirmed the position because of the close correlation of the high magnetic anomalies with features on the 19th century plan and mentioned in the accompanying report. This suggestion is further strengthened by the terracing that is still visible on the surface of the field and confirmed by the results of the 2002 fieldwalking programme.

The D-shaped enclosure is probably Iron Age in date and there is some indication that at least one of the Roman buildings utilised part of the existing Iron Age enclosure system. It is possible therefore that there was continuity of occupation on the site between the two periods and indeed that, as seems probable, the Roman buildings are of more than one phase. Only excavation is likely to resolve these and other points on this most unusual site.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Neville Cherriman, the landowner, for permission to carry out the survey and Mr Richard Massey and Mrs Ann Clark of English Heritage for arranging Scheduled Monument Consent for the work.

References

Cooper, T S, Gower, J L, & Gower, M, 1984 The Roman villa at Whitebeech, Chiddingfold: excavations in 1888 and subsequently, Surrey Archaeol Collect, 75, 57–83

Graham, D, 2005 Trial work on a Roman building complex at Chiddingfold, Surrey Archaeol Soc Bull, 388, 2–3 (full report deposited with with SCC Historic Environment Record, Woking and Surrey Archaeological Society, Guildford)

Howe, T, with Graham, D, & Graham, A, 2002 Whitebeech Roman site, Chiddingfold, Surrey: archaeological fieldwalking, unpublished report deposited with SCC Historic Environment Record, Woking and Surrey Archaeological Society, Guildford